merde alors

- 10 Posts

- 393 Comments

1·5 days ago

1·5 days agoyes, the example below is just a quick search and rotate on my phone. it’s not “great”.

what feeling were you trying to invoke by not having the ground beneath the feet of the viewer?

i wanted to transform lambda lemmings to art critics. I wanted to invoke an irresistible urge to comment

1·5 days ago

1·5 days agoIt makes it neither artistic nor cool.

being “artistic or cool” may be your goal, but they’re not universal goals.

there is no justifiable reason to have an off-level horizon.

art doesn’t need to justify.

Instead, the content of the photo should complement the rotation

that’s an awful example. Not even mediocre 🤮

you see, de gustibus non est disputandum

U.S. should invade Las Vegas too and rename it “The Meadows”.

3·5 days ago

3·5 days agoit was easier to read outside before the portable Bluetooth speakers

probably there would be no challenges for Satan in hell. Those souls would already belong to Satan. Any “day” Satan would have in hell would be a bad day.

Satan would have good days among us, the living. Tempting us. Imagine how much fun Satan would have now with a little influence in White House: Now, you should invade Canada and take Gaza, don’t you think?

36·6 days ago

36·6 days agoyou can just subscribe and see for yourself

21·6 days ago

21·6 days agowhy?

I’ve taken many photographs with non horizontal horizons. When the composition is more important than documentation, you can rotate the horizon any way you like

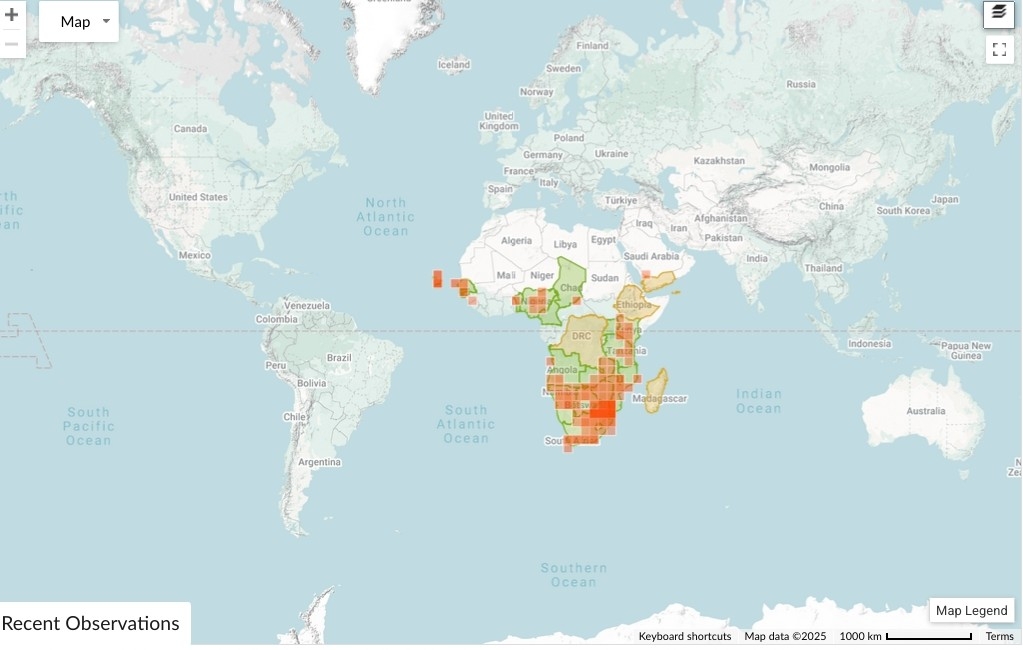

anybody from South Africa to reply to this?

or is this about the apartheid in Israel/Palestine?

In 1944, during World War II, the term was first applied to the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and the United States. During the Cold War, the British Empire dissolved, leaving the United States and the Soviet Union to dominate world affairs. At the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the United States became the world’s sole superpower, a position sometimes referred to as that of a “hyperpower”. Since the late 2010s and into the 2020s, China has increasingly been described as an emerging superpower or even an established one, as China represents the “biggest geopolitical test of the 21st century” to the United States, as it is “the only country with enough power to jeopardize the current global order”.

281·9 days ago

281·9 days agoyou mean the peace fest of 2020 when lovely americans came out to protect their capital from democracy?

they were heroes according to the current potus

is this /s ? USA is so fucked up, i don’t know what’s funny anymore 🤷

or they changed. 30 years is a long time.

their debut was released

- 3 years after the fall of Berlin wall

- a year after the dissolution of USSR

- 9 years before the September 11 attacks

- 15 years before iPhone

- 24 years before the election of a reality tv entertainer/real estate conman as POTUS

- China wasn’t a superpower back then

- EU didn’t exist in its current form

- Apartheid was still an actuality

- internet wasn’t omnipresent

3·10 days ago

3·10 days agoi feel your pain and disillusionment but it is what it is. The real “asshole” is changing the world with his Sharpie.

Good luck to you for the next 4 years

20·10 days ago

20·10 days ago☞ We knew this as soon as they got the “Don’t be evil” slogan

if you need to remind yourself not to be evil, that’s already a bad start.

21·10 days ago

21·10 days agoI mean Plato thought reading books would make people more stupid.

not true. This can help you 👇

from Phaedrus, Discussion of rhetoric and writing

This final critique of writing with which the dialogue concludes seems to be one of the more interesting facets of the conversation for those who seek to interpret Plato in general; Plato, of course, comes down to us through his numerous written works, and philosophy today is concerned almost purely with the reading and writing of written texts. It seems proper to recall that Plato’s ever-present protagonist and ideal man, Socrates, fits Plato’s description of the dialectician perfectly, and never wrote a thing.

again from the Wikipedia page:

They go on to discuss what is good or bad in writing. Socrates tells a brief legend, critically commenting on the gift of writing from the Egyptian god Theuth to King Thamus, who was to disperse Theuth’s gifts to the people of Egypt. After Theuth remarks on his discovery of writing as a remedy for the memory, Thamus responds that its true effects are likely to be the opposite; it is a remedy for reminding, not remembering, he says, with the appearance but not the reality of wisdom. Future generations will hear much without being properly taught, and will appear wise but not be so, making them difficult to get along with.

No written instructions for an art can yield results clear or certain, Socrates states, but rather can only remind those that already know what writing is about. Furthermore, writings are silent; they cannot speak, answer questions, or come to their own defense.

Accordingly, the legitimate sister of this is, in fact, dialectic; it is the living, breathing discourse of one who knows, of which the written word can only be called an image. The one who knows uses the art of dialectic rather than writing:

“The dialectician chooses a proper soul and plants and sows within it discourse accompanied by knowledge—discourse capable of helping itself as well as the man who planted it, which is not barren but produces a seed from which more discourse grows in the character of others. Such discourse makes the seed forever immortal and renders the man who has it happy as any human being can be.”

☞ Phaedrus on Project Gutenberg

1·10 days ago

1·10 days ago“on X”

3·10 days ago

3·10 days agoulrich!

now you are lars ulrich. How many ulrichs can you be?

4·10 days ago

4·10 days agopotus is the “head of government”. Would you prefer @[email protected] to write “head of government of the USA has changed the name”?

give them a break!

i use notally for quick notes and reminders but i needed another organizer for longer text

i started trying notesnook after reading your comment and it looks like what i needed. I really like its customizability. I wish there was an option to choose fonts from file.

The only problem is that constant login reminder. Is there a way to get rid of it?